A seasonal scientific blog was the order of the day, and with the holidays approaching I couldn’t resist looking in to the chemistry of roast potatoes…

As far as my family are concerned, the crowning glory of any Christmas dinner is the humble roast potato. There was almost a riot a few years ago when (for a family dinner with eight guests eating) I only made enough roasties for a family of approximately fifteen. I’ve been politely informed not to pull that kind of stunt again if we’re eating together this year…

So, what makes a roast potato amazing? It has to have a seriously crispy outside with lots of messy edges all frazzled but the inside has to be melt-in-the-mouth fluff. I’m renowned amongst my family for the quality of my roasties, but I wanted to know the chemistry behind the results and find out if there was a fool proof scientific route to achieving them so here we go for the chemistry of roast potatoes.

Back to their roots and why the chemistry of roast potatoes actually matters

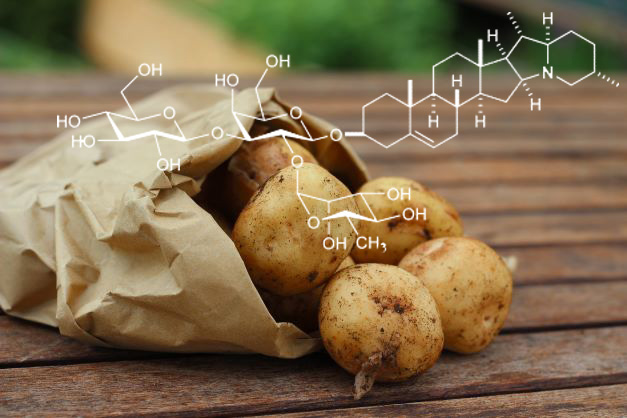

Let’s start at the beginning. The potato, or Solanum tuberosum L. is actually part of the nightshade family and the vegetative and fruiting parts of it contain the toxin solanine which is dangerous for human consumption. Those who grow their own potatoes will be well aware that you wait until the plants die off before digging your potatoes up, but if they’re green when you lift them you must not eat them. A little potato juice can be used in medicinal practices such as treatment of peptic ulcers and relief from pain and acidity but excessive amounts of it can be toxic. A poultice from boiling potatoes in water can help rheumatic joints, swellings, skin rashes and even haemorrhoids but uncooked potatoes can be used as a soothing plaster for burns and scalds.

Solanine: toxic effects seen at 1000 MC/KG of body weight

As I’m sure you’re aware though, a potato is a tuber. This basically means that you can plant it in soil and grow more potatoes. It also means that it’s technically alive therefore the first step towards achieving roast potato heaven is (and this sounds a bit brutal, sorry…) is actually to kill it. How ever you choose to heat your potato to do so, this process inactivates the enzymes contained within it that allow it to function as a tuber.

Depending on which potatoes you’re using – and there are hundreds of varieties to choose from – there are going to be different qualities which are suited to particular methods of cooking. Here in the UK, we tend to use a Maris Piper or something similar for a roast, whereas I believe the popular choice for the US is the Russet potato. Whichever variety you’re using, the cells inside all have the same basic structure: each cell contains a sack of water, a nucleus, and various other structures to keep the cells running. Around each cell is a wall which protects the inside. It’s these walls that hold everything together and keep the potato firm via a phenomenon called turgor (water within presses against the cell walls. If the potato dries out and loses moisture it will become soft). Cooking causes this cell wall to rupture and the starch grains within swell, and eventually begin to disperse. This gives us the beginning of the soft and fluffy centre we want.

I should mention that the greater the surface area in contact with your roasting pan, the more opportunity there is for it to become crisp and delicious. Cutting your potatoes to increase the surface area is a great tip, but I also like to keep my roasties fairly small as they crisp up better. Researchers at a UK school found that by cutting your potatoes at 30° angles is far more effective at increasing surface area than the more usual 90°. (You can see their findings HERE.)

Once par-boiled for around 10 minutes in salted water (you could also add ½ teaspoon baking powder to this to help break down the starch) on a rolling simmer the potatoes need to be drained and then agitated (or “shiggled” as we call it in our house) to loosen up the rigid edges of the potatoes. Then leave the lid off your drained pan of potatoes and allow the steam to dissipate. This makes those edges less waterlogged and better able to crisp during roasting. A group in the US did a light-hearted video study of what impact the pH of your water has on your end results and it was interesting to see that they found a “regular” water or slightly alkaline water gave you the best end product whereas an acidic water gave you a kind of hard, chewy, roast potato which doesn’t sound like a joy to eat so don’t go adding vinegar to your water!

The next step is where we hope to achieve the Maillard reaction and produce the best roast potatoes your family will have ever seen!

The Maillard reaction takes place between proteins and sugars. The higher the temperature you’re cooking at, the faster this reaction proceeds (so better to cook for a shorter time at a higher temperature than a longer time at a lower temperature). The accepted process is to tumble your par-boiled potatoes in oil (whether pre-heated or cold), add your chosen seasonings or flavourings (such as salt, pepper, herbs, spices – although some cooks add these just a few minutes before they remove the finished product from the oven) and then roast in a hot oven until crispy.

What oil or fat do you use though? For a special occasion such as Christmas (or Thanksgiving) we might choose something flavourful like duck or goose fat, but these have a much lower burning point than vegetable or sunflower oil so you have to be careful not to end up with what looks like lumps of charcoal in your roasting pan! One solution is to mix a little vegetable oil or olive oil with your chosen extravagant fat to stabilise the reaction. I add a couple of tablespoons full of goose fat and the same of sunflower oil to my roasting tray and heat for around ten minutes at 200 °C before I carefully add the potatoes and turn them in the fat to baste them. Give each piece of potato some space – don’t crowd them – and make sure at least one side is resting fully on the base of the pan. Pop them in the oven to cook for 20 minutes and then take them out and carefully turn them over. Return to the oven quickly. After another 20 minutes (sometimes 30) they’re perfectly crispy and you’ll be fending your families forks off your amazing roast potatoes!

There you have it – the chemistry of roast potatoes!

Handy tip: if you’re cooking turkey (or even a huge chicken) then do your potato prep ready for the period while your bird is resting. Cover the turkey in foil (shiny side on the inside) and a couple of clean tea towels and leave it to one side and it will be delicious and succulent once your roast potatoes are ready. This also means that if you’re catering for vegetarian or vegan guests, your potatoes are cooked separately from the meat so everyone can enjoy them. There’s plenty of space in the oven for other veggies, cauliflower cheese, nut loaf or anything else too and you’re not rushing and panicking about getting everything out of your oven at once. #ChristmasWin

Alternative methods

British chef, restaurateur, and author Jamie Oliver, is adamant that by using a potato masher or a fish slice to squash the roast potatoes a little to increase their contact with the roasting pan we achieve much better roast potatoes. Personally, I don’t want my roast potatoes looking like someone sat on them but that’s just my opinion! You can see his method HERE.

Gordon Ramsey (renowned for being a brilliant chef, restaurateur and author too but mostly for having a terrible potty mouth) adds semolina to his parboiled potatoes before roasting them but otherwise does them in much the same way I do. I’ve never tried this myself – have you? You can see his method HERE.

Controversially, the fabulous US celebrity food writer and presenter, Ina Garten (otherwise known as the Barefoot Contessa) doesn’t parboil her potatoes which I was hugely shocked to discover! You can see how she prepares them HERE.

I hope you enjoyed reading!

I hope our look at the chemistry of roast potatoes has been useful to you but if you’d like to be sure you never miss one of our chemistry blogs, including our “Behind the flask” interview series, then register now to receive our monthly newsletter by email. You can do this in just a few seconds here: https://www.asynt.com/newsletter/