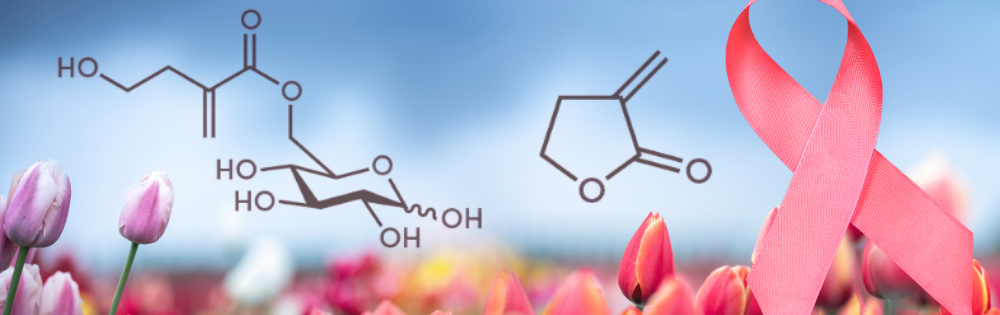

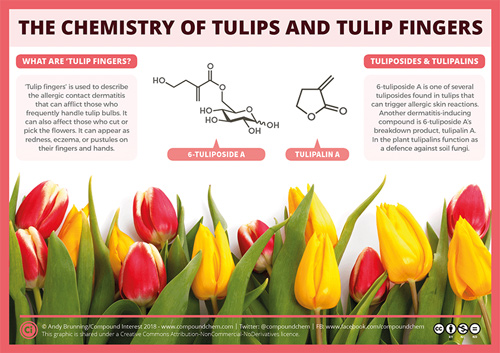

The chemistry of tulips is complicated and a bit of a mixture of good and bad. From my teen years working in a garden centre, I can tell you that if you handle the bulbs a lot you’re going to probably end up with something known as “tulip fingers” that’s a type of allergic contact dermatitis. The skin reddens and becomes inflamed. For those who work in the tulip industry, it can get more extreme – even causing pustules.

The compounds that cause these issues are tuliposides and tulipalins and are both found in the sap and the tulip bulbs.

Those helpful folks at Compound Interest tell us:

“Tulips make tuliposides from a combination of glucose and other organic compounds. Tulipalins form when tuliposides break down. Both compounds can trigger allergic skin reactions, and tulipalin A is a key causative agent. Chemical groups in skin proteins attack parts of these molecules, making substances that lead to an immune response in the body. This is the allergic reaction that ‘tulip fingers’ refers to.”

They go on to explain that tuliposides break down to form tulipalins when soil fungi attack the tulip – this then acts as a strong antifungal effect to combat infection.

This got me wondering if there were other possible uses for those compounds and, unsurprisingly, I wasn’t the first to do so… After some routing around the internet I discovered an interesting paper from a number of authors in Turkey that I felt our readers may find interesting:

Cytotoxic and bioactive properties of different colour tulip flowers and degradation kinetic of tulip flower anthocyanins

The study was carried out to determine the potential use of anthocyanin-based extracts (ABEs) of wasted tulip flowers as natural food/drug colourants as there is a great volume of available material in Turkey. The authors discovered that total anthocyanin levels were higher than in other flowers, and the extracts were more effective for the inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Yersinia enterocolitica compared to other tested bacteria. What I found particularly fascinating though, was that the cytotoxic effects of five different tulip flower extracts impact on human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7*) cell line were investigated. Results indicated that whilst orange, red, pink and violet extracts had to cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 cell lines, yellow and claret red extracts appeared to be toxic for the cells!

The team summarised, saying that overall, the extracts of tulip flowers with different colours possess remarkable bioactive and cytotoxic properties. Perhaps it’s worth putting up with the odd case of “tulip fingers” after all as they’re not just pretty flowers it seems…

*MCF-7 is a breast cancer cell line isolated in 1970 from a 69-year-old White woman. MCF-7 is the acronym of Michigan Cancer Foundation-7, referring to the institute in Detroit where the cell line was established in 1973 by Herbert Soule and co-workers.

What are you working on?

We would love to know if you’ve published a paper after running reactions using any of your Asynt lab equipment. Is there a topic you’d like to share with us? It could potentially be published in our Case Studies area, used as a press release and translated & published in four languages worldwide, and featured in our monthly newsletter. You’re most welcome to speak with your regular Asynt account manager or contact the marketing team via email to [email protected]

Carry on reading:

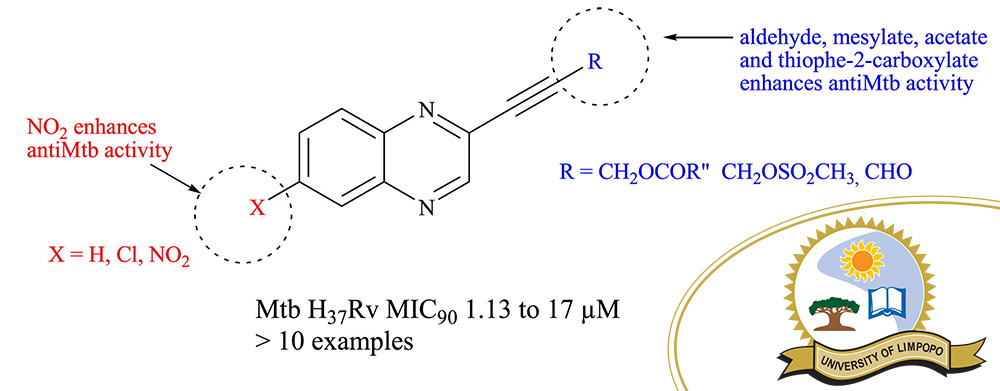

Dr Tlabo Leboho, a researcher at the University of Limpopo in South Africa, shares details about their research into anti-tuberculosis agents and the people behind the flask. Click HERE to read.

Sources: Compound Interest | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23712096/